Journal

A corkscrew doesn’t have to be boring!

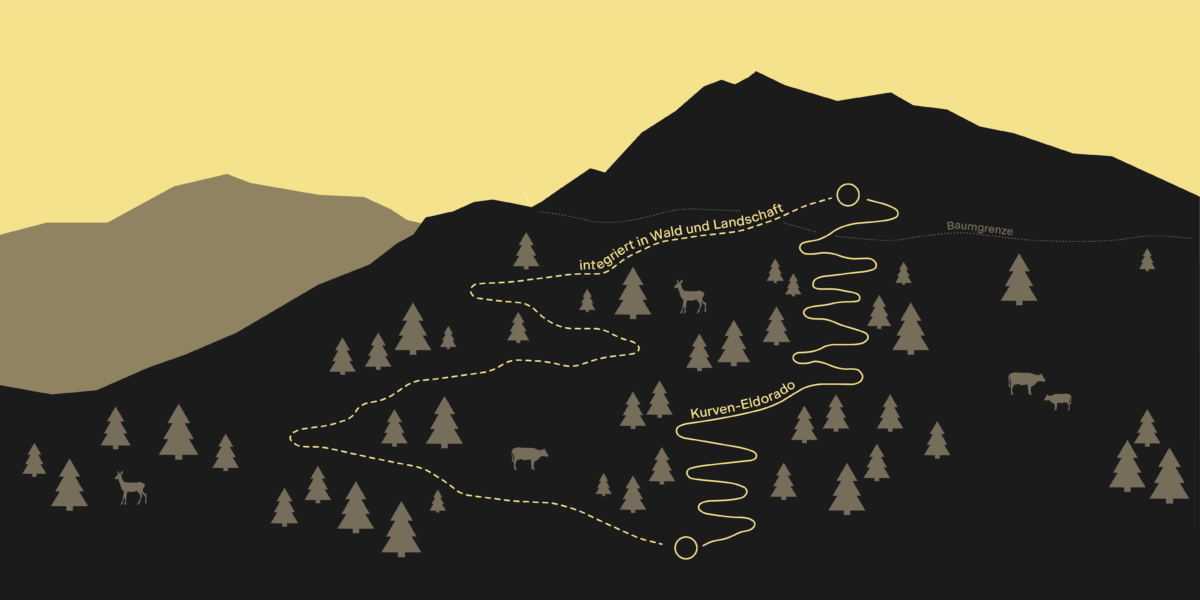

Using the Forest Bump Trail in the Bellwald Bike Park as an example, we take a brief excursion into spatial planning and forest law. In tourist areas, trails below the tree line are often squeezed into non-forested areas. Why is this the case? How can good planning and construction solutions still be developed? And why it is sometimes still worth persisting …

Author: Severin Schindler

Images: Philipp Bont, Fabrice Burgener, Thomas Stöckli, Cédric Baumer, Romanée Nieuwland

Location constraints what?

In terms of spatial planning, a construction project is always location-specific if it is dependent on the location for objective reasons – be it outside the building zone or in the forest. Financial or subjective reasons may not be decisive. If there are unstocked areas within the planning perimeter (these are usually cleared areas such as cultivated pastures, ski slopes or lift tracks), these are to be given preference over the forest if a line layout is structurally possible and there are no overriding interests to the contrary (e.g. a fen, cultivation, etc.).

Please not in the forest!

This was also the case with the Forest Bump Trail. The trail could only rarely be run with long straights through the forest. In the second half of the trail, a height difference of around 140 metres – i.e. more than ⅓ of the total height difference – has to be overcome via 25 successive berms in the cleared track of the 6-seater chairlift. However, approach curves mean significantly higher construction costs. The steeper the slope inclination, the more soil displacement is required. While the first half of the curve is built into the existing terrain on the uphill side, the second half has to be backfilled and compacted on the downhill side. This can result in embankments up to 3 metres high on the downhill side. This makes the trail much more visible in the landscape when viewed from the front. Careful revegetation of the embankments is therefore all the more important in order to integrate the trail into the topography in the best possible way and avoid erosion.

A boring Eldorado of bends?

By no means! Challenging conditions demand and force the trail builders to make the most of a compact layout. The tricky question is, how do you make a seemingly boring marble run exciting? Two points are central:

- A varied and coherent design of curves and straights: Every straight is different and can be varied with different ingredients such as rollers, scrub waves, side hits on both the valley and mountain sides, slight changes of direction, rock formations or jumps. For 180° changes of direction, we implement varied, creative and situation-appropriate shapes that ensure great feelings in the turns.

- The speed in the straights must be harmonised with the curves. Excessive inclination can lead to brake bumps. The entry speed is set so that you don’t have to brake in the bend, but also so that you have enough speed for the next straight and its features.

Ideally, every 180° bend heralds a new mini-experience in a straight. These mini-experiences ultimately come together to form a coherent overall picture.

Advantages and disadvantages

Overall, compact corridor planning outside the forest can certainly have advantages. However, like many things in this world, it also has a range of disadvantages:

Advantages:

- Opportunity for creative trail design – turning necessity into a virtue

- if under the lift line: watching and cheering from the lift (social component)

- less fragmentation of habitat due to overlapping use or concentration of infrastructure

- less restriction in forest management

Disadvantages:

- higher construction costs

- visible impact on the landscape

- high maintenance costs due to the many bends

- trail is not protected by the forest (drought + heavy precipitation)

- if on ski slope: no major terrain shifts possible (snow groomer compatibility)

- line layout can be too steep depending on the situation (not sustainable)

- monotonous trail design results in a boring riding experience

Logically, the disadvantages listed here are often also arguments in favour of creating the trail in the forest (e.g. integration into the landscape, protection from the weather, etc.). In our view, the disadvantages in favour of a location outside the forest usually outweigh the disadvantages. However, the great art is to cope with these framework conditions. But only to a certain extent …

Stubbornly setting the course in planning

In the Central Plateau, where mountain biking mainly takes place, it is less difficult to argue for the location of forests than in higher tourist areas. In this context, the forest functions, which are often defined as areas in forest plans, are always a decisive spatial planning factor. The four forest functions are: Recreation, production, protection and habitat. While areas with the ‘recreation function’ provide good spatial planning conditions for mountain bike trails, the two functions of protection forest and habitat in particular are limiting factors at higher altitudes and are often directly related (e.g. protection forest and game browsing). Nonetheless, due to various protection and utilisation interests, it is seldom a good idea to build a line exclusively outside the forest. A balanced approach is required from all stakeholders in order to ultimately be able to jointly define a functional route in terms of guidance and attractiveness.

One example where we were able to work out a good solution is the popular forest section in the second part of the Into the Wild Trail (also in the Bellwald Bike Park). Instead of following the flat ski slope for longer and then reducing the altitude over a steep section, a former trail with a regular gradient in the forest was reactivated. And lo and behold, this section (see picture below) is one of the highlights of the Bellwald Bike Park.